lost spring

Storyboard Text

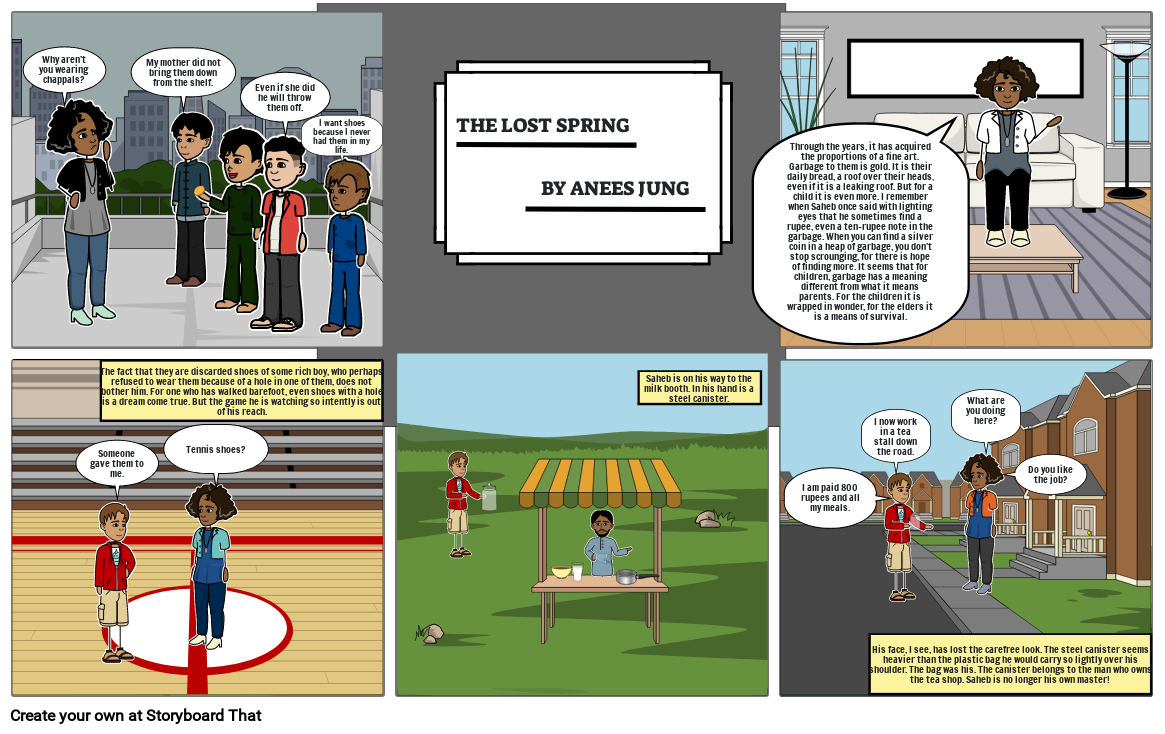

- Why aren’t you wearing chappals?

- My mother did not bring them down from the shelf.

- Even if she did he will throw them off.

- I want shoes because I never had them in my life.

- THE LOST SPRING

- BY ANEES JUNG

- Through the years, it has acquired the proportions of a fine art. Garbage to them is gold. It is their daily bread, a roof over their heads, even if it is a leaking roof. But for a child it is even more. I remember when Saheb once said with lighting eyes that he sometimes find a rupee, even a ten-rupee note in the garbage. When you can find a silver coin in a heap of garbage, you don’t stop scrounging, for there is hope of finding more. It seems that for children, garbage has a meaning different from what it means parents. For the children it is wrapped in wonder, for the elders it is a means of survival.

- Someone gave them to me.

- The fact that they are discarded shoes of some rich boy, who perhaps refused to wear them because of a hole in one of them, does not bother him. For one who has walked barefoot, even shoes with a hole is a dream come true. But the game he is watching so intently is out of his reach.

- Tennis shoes?

- Saheb is on his way to the milk booth. In his hand is a steel canister.

- I now work in a tea stall down the road.

- His face, I see, has lost the carefree look. The steel canister seems heavier than the plastic bag he would carry so lightly over his shoulder. The bag was his. The canister belongs to the man who owns the tea shop. Saheb is no longer his own master!

- I am paid 800 rupees and all my meals.

- What are you doing here?

- Do you like the job?

Over 30 Million Storyboards Created