Story board

Storyboard Text

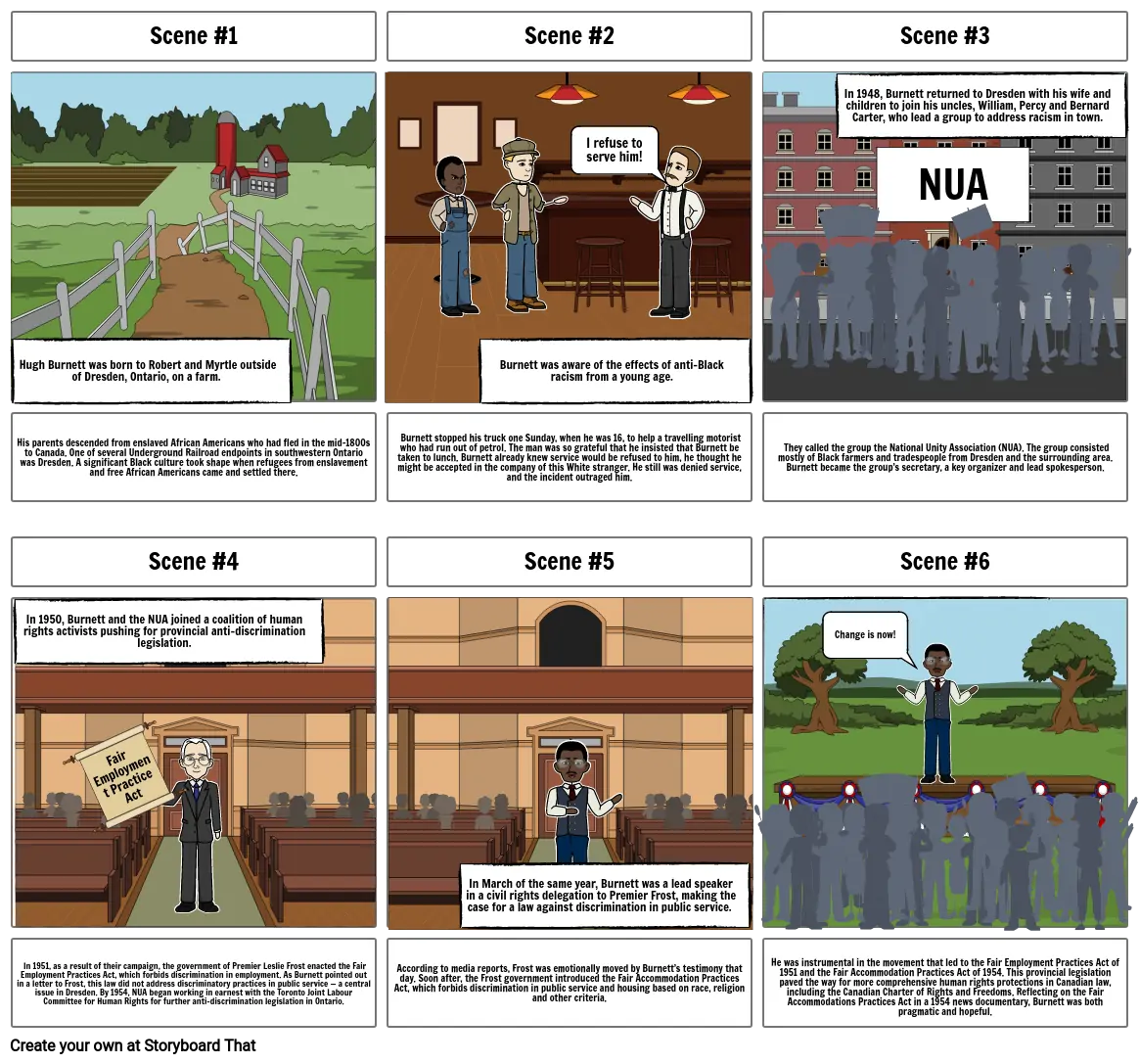

- Hugh Burnett was born to Robert and Myrtle outside of Dresden, Ontario, on a farm.

- Scene #1

- Scene #2

- Burnett was aware of the effects of anti-Black racism from a young age.

- I refuse to serve him!

- Scene #3

- In 1948, Burnett returned to Dresden with his wife and children to join his uncles, William, Percy and Bernard Carter, who lead a group to address racism in town.

- NUA

- His parents descended from enslaved African Americans who had fled in the mid-1800s to Canada. One of several Underground Railroad endpoints in southwestern Ontario was Dresden. A significant Black culture took shape when refugees from enslavement and free African Americans came and settled there.

- Scene #4

- In 1950, Burnett and the NUA joined a coalition of human rights activists pushing for provincial anti-discrimination legislation.

- Burnett stopped his truck one Sunday, when he was 16, to help a travelling motorist who had run out of petrol. The man was so grateful that he insisted that Burnett be taken to lunch. Burnett already knew service would be refused to him, he thought he might be accepted in the company of this White stranger. He still was denied service, and the incident outraged him.

- Scene #5

- Hugh Burnett was a prominent person for change in his community and the fight for human rights legislation in Ontario.

- They called the group the National Unity Association (NUA). The group consisted mostly of Black farmers and tradespeople from Dresden and the surrounding area. Burnett became the group’s secretary, a key organizer and lead spokesperson.

- Scene #6

- Change is now!

- In 1951, as a result of their campaign, the government of Premier Leslie Frost enacted the Fair Employment Practices Act, which forbids discrimination in employment. As Burnett pointed out in a letter to Frost, this law did not address discriminatory practices in public service — a central issue in Dresden. By 1954, NUA began working in earnest with the Toronto Joint Labour Committee for Human Rights for further anti-discrimination legislation in Ontario.

- Fair Employment Practice Act

- According to media reports, Frost was emotionally moved by Burnett’s testimony that day. Soon after, the Frost government introduced the Fair Accommodation Practices Act, which forbids discrimination in public service and housing based on race, religion and other criteria.

- In March of the same year, Burnett was a lead speaker in a civil rights delegation to Premier Frost, making the case for a law against discrimination in public service.

- He was instrumental in the movement that led to the Fair Employment Practices Act of 1951 and the Fair Accommodation Practices Act of 1954. This provincial legislation paved the way for more comprehensive human rights protections in Canadian law, including the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Reflecting on the Fair Accommodations Practices Act in a 1954 news documentary, Burnett was both pragmatic and hopeful.

Over 30 Million Storyboards Created