Unknown Story

Storyboard Text

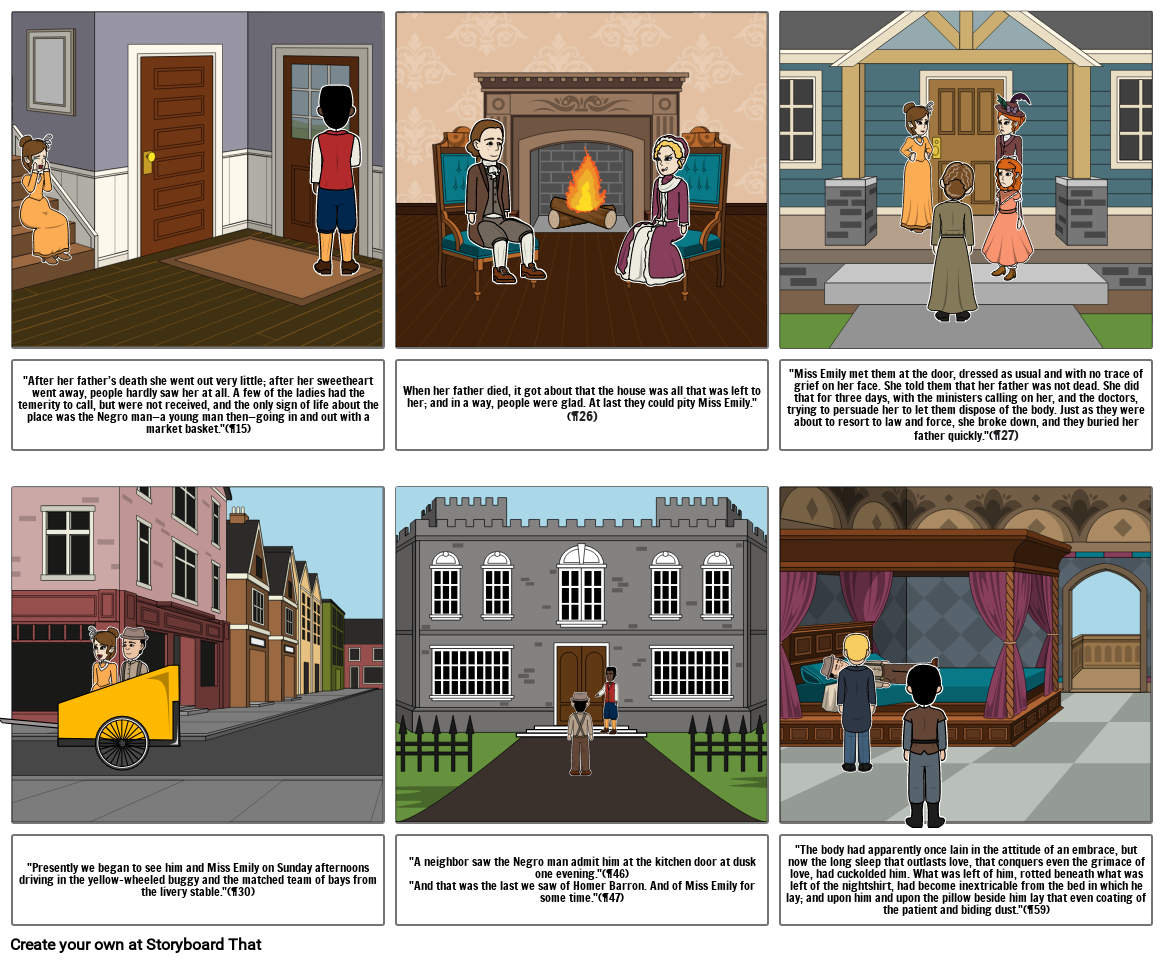

- After her father’s death she went out very little; after her sweetheart went away, people hardly saw her at all. A few of the ladies had the temerity to call, but were not received, and the only sign of life about the place was the Negro man—a young man then—going in and out with a market basket.(¶15)

- When her father died, it got about that the house was all that was left to her; and in a way, people were glad. At last they could pity Miss Emily. (¶26)

- Miss Emily met them at the door, dressed as usual and with no trace of grief on her face. She told them that her father was not dead. She did that for three days, with the ministers calling on her, and the doctors, trying to persuade her to let them dispose of the body. Just as they were about to resort to law and force, she broke down, and they buried her father quickly.(¶27)

- Presently we began to see him and Miss Emily on Sunday afternoons driving in the yellow-wheeled buggy and the matched team of bays from the livery stable.(¶30)

- A neighbor saw the Negro man admit him at the kitchen door at dusk one evening.(¶46)And that was the last we saw of Homer Barron. And of Miss Emily for some time.(¶47)

- The body had apparently once lain in the attitude of an embrace, but now the long sleep that outlasts love, that conquers even the grimace of love, had cuckolded him. What was left of him, rotted beneath what was left of the nightshirt, had become inextricable from the bed in which he lay; and upon him and upon the pillow beside him lay that even coating of the patient and biding dust.(¶59)

Over 30 Million Storyboards Created