Tuck Everlasting — Gaia M.

Storyboard Text

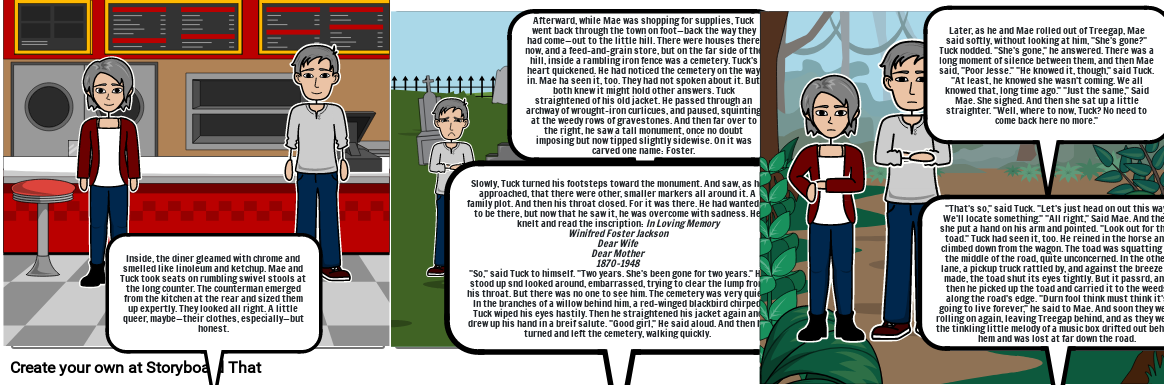

- Inside, the diner gleamed with chrome and smelled like linoleum and ketchup. Mae and Tuck took seats on rumbling swivel stools at the long counter. The counterman emerged from the kitchen at the rear and sized them up expertly. They looked all right. A little queer, maybe—their clothes, especially—but honest.

- Slowly, Tuck turned his footsteps toward the monument. And saw, as he approached, that there were other, smaller markers all around it. A family plot. And then his throat closed. For it was there. He had wanted it to be there, but now that he saw it, he was overcome with sadness. He knelt and read the inscription: In Loving MemoryWinifred Foster JacksonDear WifeDear Mother1870-1948"So," said Tuck to himself. "Two years. She's been gone for two years." He stood up snd looked around, embarrassed, trying to clear the lump from his throat. But there was no one to see him. The cemetery was very quiet. In the branches of a willow behind him, a red-winged blackbird chirped. Tuck wiped his eyes hastily. Then he straightened his jacket again and drew up his hand in a breif salute. "Good girl," He said aloud. And then he turned and left the cemetery, walking quickly.

- Afterward, while Mae was shopping for supplies, Tuck went back through the town on foot—back the way they had come—out to the little hill. There were houses there now, and a feed-and-grain store, but on the far side of the hill, inside a rambling iron fence was a cemetery. Tuck's heart quickened. He had noticed the cemetery on the way in. Mae ha seen it, too. They had not spoken about it. But both knew it might hold other answers. Tuck straightened of his old jacket. He passed through an archway of wrought-iron curlicues, and paused, squinting at the weedy rows of gravestones. And then far over to the right, he saw a tall monument, once no doubt imposing but now tipped slightly sidewise. On it was carved one name: Foster.

Over 30 Million Storyboards Created