Unknown Story

Storyboard Text

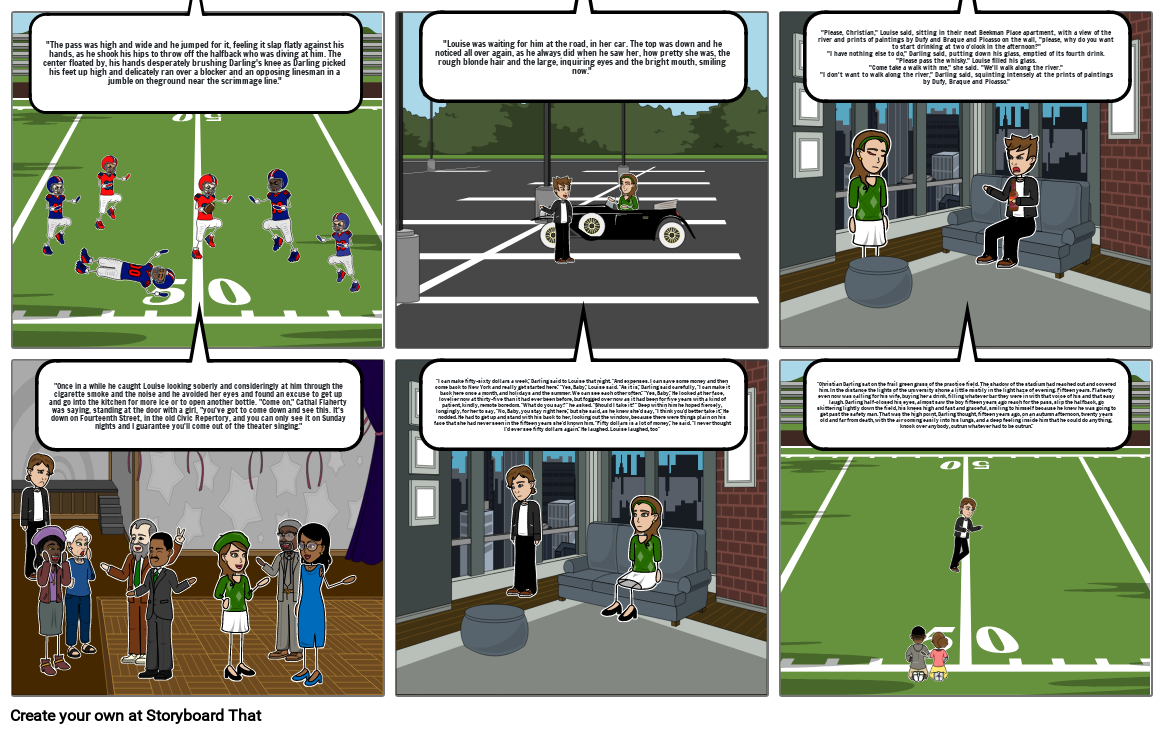

- The pass was high and wide and he jumped for it, feeling it slap flatly against his hands, as he shook his hips to throw off the halfback who was diving at him. The center floated by, his hands desperately brushing Darling's knee as Darling picked his feet up high and delicately ran over a blocker and an opposing linesman in a jumble on theground near the scrimmage line.

- Louise was waiting for him at the road, in her car. The top was down and he noticed all over again, as he always did when he saw her, how pretty she was, the rough blonde hair and the large, inquiring eyes and the bright mouth, smiling now.

- Please, Christian, Louise said, sitting in their neat Beekman Place apartment, with a view of the river and prints of paintings by Dufy and Braque and Picasso on the wall, please, why do you want to start drinking at two o'clock in the afternoon? I have nothing else to do, Darling said, putting down his glass, emptied of its fourth drink. Please pass the whisky. Louise filled his glass. Come take a walk with me, she said. We'll walk along the river. I don't want to walk along the river, Darling said, squinting intensely at the prints of paintings by Dufy, Braque and Picasso.

- Once in a while he caught Louise looking soberly and consideringly at him through the cigarette smoke and the noise and he avoided her eyes and found an excuse to get up and go into the kitchen for more ice or to open another bottle. Come on, Cathal Flaherty was saying, standing at the door with a girl, you've got to come down and see this. It's down on Fourteenth Street, in the old Civic Repertory, and you can only see it on Sunday nights and I guarantee you'll come out of the theater singing.

- I can make fifty-sixty dollars a week, Darling said to Louise that night. And expenses. I can save some money and then come back to New York and really get started here. Yes, Baby, Louise said. As it is, Darling said carefully, I can make it back here once a month, and holidays and the summer. We can see each other often. Yes, Baby. He looked at her face, lovelier now at thirty-five than it had ever been before, but fogged over now as it had been for five years with a kind of patient, kindly, remote boredom. What do you say? he asked. Should I take it? Deep within him he hoped fiercely, longingly, for her to say, No, Baby, you stay right here, but she said, as he knew she'd say, I think you'd better take it. He nodded. He had to get up and stand with his back to her, looking out the window, because there were things plain on his face that she had never seen in the fifteen years she'd known him. Fifty dollars is a lot of money, he said. I never thought I'd ever see fifty dollars again. He laughed. Louise laughed, too

- Christian Darling sat on the frail green grass of the practice field. The shadow of the stadium had reached out and covered him. In the distance the lights of the university shone a little mistily in the light haze of evening. Fifteen years. Flaherty even now was calling for his wife, buying her a drink, filling whatever bar they were in with that voice of his and that easy laugh. Darling half-closed his eyes, almost saw the boy fifteen years ago reach for the pass, slip the halfback, go skittering lightly down the field, his knees high and fast and graceful, smiling to himself because he knew he was going to get past the safety man. That was the high point, Darling thought, fifteen years ago, on an autumn afternoon, twenty years old and far from death, with the air coming easily into his lungs, and a deep feeling inside him that he could do anything, knock over anybody, outrun whatever had to be outrun.

Over 30 Million Storyboards Created

No Downloads, No Credit Card, and No Login Needed to Try!